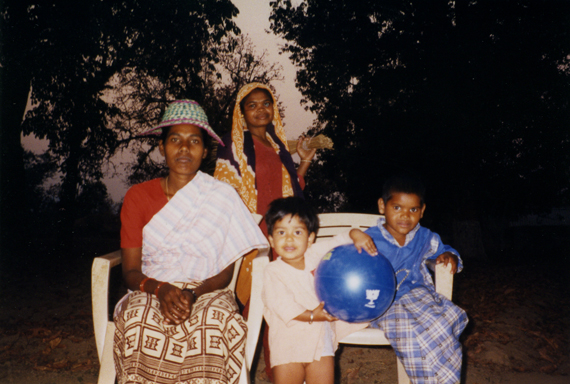

The rural society settles in the town and is confronted at the same time with the violent process of integration and assimilation and with the social problems resulting from the arbitrary management of country by the makhzenian Mafia. This situation requires the invention of new forms of poetico-musical expressions (or the adaptation of the old forms) to express at the same time the nostalgia of the origins and the anger towards the abusive policies. Also, at this times, Anglo-Saxon musical groups (such as the Beatles) as well as Moroccan groups (Nass el Ghiwan, Jil Jilala, etc.) impose their rhythms and influence the development of musical groups known as popular. Mixing modern and traditional instruments, these groups interpret songs, inspired by the ancestral tradition or expressing the current sensibilities of a generation coming from the first wave of the rural emigrants.

Founded at the end of the Sixties by a group of young people from newly urbanized families, Izenzarn is among the first Amazigh groups to modernize and radicalize the Amazigh song. After tribulations under different names, a first album is recorded in the year 1974. Thus starts the first season of the group, characterized by love songs such as: Wad ittemuddun (traveler), Wa zzin (Oh! beauty), etc, or nostalgic and traditional songs: Immi Henna (My gracious mother)... In the beginning of the Eighties, Izenzarn embraces more protesting themes: ttuzzalt (dagger), ttâbla (plate), tamurghi (grasshoppers)...

The protest in Izenzarn's songs is characterized by the challenge of the dominant speeches:

Iggut lebrîh idrus may sellan igh islêh

Plenty of speeches And yet Nobody listens to the reason

and the harsh description of the reality:

Nettghwi zun d teghwi tmmurghi gh igenwan ikk d lhif akal

We are like grasshoppers taken between the skies and the dry grounds.

This reality is a world of fear, oppression and torture [tawda gh will ugharas (fear in the paths), izîtti wuzzal (iron bars), ur nemmut ur nsul (neither alive nor dead)]

The success of the group is due to its strange musical style and the poetry of its songs that presented already at the end of the Seventies the germs of a revolution in the modern Berber poetic creation.

After a disagreement, the group had split. Two groups dispute the name: Izenzarn Iggut Abdelhadi and Izenzarn Shamkh. But, it is the first one that imposed itself due to the emblematic image of its main singer, Iggut Abdelhadi.